New to Propagate Lab: check out our Seltzer Kit containing everything needed to make an award-winning seltzer!

Lesson 7: Fermentation and Finishing

Module 7, Part A: Yeast

The Heart of Fermentation

Yeast is the powerhouse of brewing—transforming wort into beer through fermentation.

In this module, you’ll explore what yeast is, how it works, the diversity of strains used

in brewing, and best practices for yeast health and management.

- Explain the importance of yeast in brewing

- Identify major yeast-cell components and their functions

- Differentiate types and strains of brewing yeast

- Understand the yeast life cycle and growth phases

- List key requirements for healthy yeast performance

- Explain the role and benefits of dry yeast in brewery settings

Why Yeast Matters

Yeast is a single-celled fungus responsible for one of the most important transformations in brewing:

converting sweet wort into beer. By consuming simple sugars, yeast produces alcohol, CO₂, and a wide

range of flavor-active metabolites that define a beer’s character.

Beyond alcohol and carbonation, yeast produces esters, phenols,

organic acids, and other compounds that influence aroma, mouthfeel, and stability.

Managing yeast health is as critical as selecting malt, hops, or water—healthy yeast means

clean, reliable, and flavorful beer.

The Yeast Cell

Yeast cells are eukaryotes, meaning they contain membrane-bound organelles and a nucleus.

Each structure plays a key role in how yeast grows, ferments, and responds to stress in the brewhouse.

- Cell wall: Provides rigidity, protects the cell, and influences flocculation behavior.

- Plasma membrane: Regulates nutrient transport, alcohol tolerance, and stress response.

- Nucleus: Contains DNA that determines strain-specific traits and fermentation characteristics.

- Vacuole: Stores nutrients, helps maintain pH, and responds to environmental stress.

- Mitochondria: Provide energy (ATP), especially important during growth phases.

Understanding yeast anatomy helps brewers evaluate culture vitality, optimize oxygenation,

adjust pitching rates, and troubleshoot stalled fermentations or off-flavors.

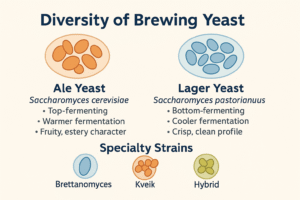

Diversity of Brewing Yeast

Brewing yeast is generally divided into two major groups:

-

Ale Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae):

Top-fermenting, thrives at warmer temperatures, and produces fruity, estery character. -

Lager Yeast (Saccharomyces pastorianus):

Bottom-fermenting, prefers cooler fermentation, and yields crisp, clean profiles.

Brewers also use specialty strains such as Brettanomyces,

Kveik, and various hybrids to achieve unique fermentation profiles.

Each strain differs in temperature range, flocculation, and flavor expression.

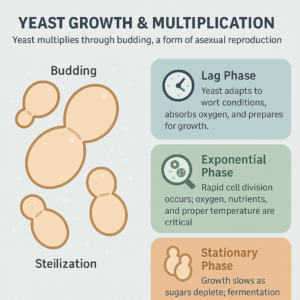

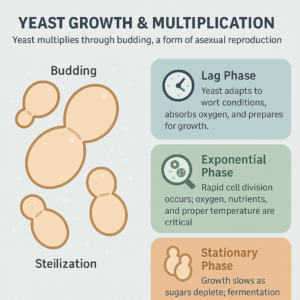

Yeast Growth & Multiplication

Yeast multiplies through budding, a form of asexual reproduction.

After pitching, cells progress through three key phases:

-

Lag Phase:

Yeast adapts to wort, absorbs oxygen, and prepares for growth. -

Exponential Phase:

Rapid cell division occurs; oxygen, nutrients, and temperature are critical. -

Stationary Phase:

Growth slows as sugars deplete; fermentation ends and yeast flocculates.

The brewer’s job is to provide oxygen, nutrients, and proper temperature

to guide yeast toward a healthy, complete fermentation.

Keeping Yeast Healthy

Yeast health is one of the strongest predictors of beer quality.

To support optimal fermentation, brewers must provide:

- Oxygen at pitching (for sterol & membrane synthesis)

- Nutrients including FAN, minerals, and zinc

- Proper temperature based on strain

- Stress management (alcohol, pH, osmotic pressure)

- Strict sanitation to prevent contamination

Cell counts, viability staining, and vitality tests help brewers monitor performance

and determine how many generations a culture can be safely reused.

Liquid vs Dry Yeast in Brewing

Brewers can choose between liquid and dry yeast, each with unique advantages.

Understanding these options helps ensure predictable, high-quality fermentation.

Liquid Yeast

- High vitality & quality — fast starts, clean flavor.

- Wide strain diversity — lagers, ales, saisons, Brett, blends.

- Ideal for precision brewing when flavor control matters.

- Short shelf life — requires refrigeration.

- Higher cost due to production & cold-chain handling.

Dry Yeast

- Very long shelf life — stable even at room temperature.

- Lower cost — ideal for large batches or simple styles.

- No starter required — pitch directly.

- Slightly higher contaminant load than high-grade liquid yeast.

- More limited strain selection compared to liquid options.

Most commercial breweries rely on liquid yeast for vitality and strain selection,

but dry yeast remains indispensable for its reliability, cost savings, and stability.

Module Summary — Yeast

Yeast is the engine of fermentation and one of the most influential contributors to beer character.

Through metabolic activity, yeast transforms wort sugars into alcohol, CO₂, and a diverse array of

flavor compounds including esters, phenols, organic acids, and sulfur compounds.

In this module, you explored the major types of brewing yeast—ale, lager, Brettanomyces,

Kveik, and hybrids—along with their fermentation profiles, temperature ranges, and flavor expression.

You learned how yeast grows through lag, exponential, and stationary phases and how proper

nutrient availability, oxygenation, and temperature control support healthy fermentation.

You also examined key aspects of yeast management including sanitation,

pitching rates, vitality testing, and generational tracking, and compared the benefits and

trade-offs of liquid vs. dry yeast in commercial brewing.

With these fundamentals, you are equipped to make informed decisions about yeast selection,

fermentation strategy, and quality control—ensuring clean, consistent, and expressive beers.

Check-In: Yeast Knowledge

Lager (S. pastorianus)

Module 7, Part B: Post-Fermentation & Packaging

Preparing Beer for Service: From Fermenter to Package

Once fermentation is complete, beer must be clarified, stabilized, carbonated, and packaged

in a way that preserves its flavor and ensures shelf stability.

In this section, you’ll learn the professional techniques used to prepare beer for kegs, cans,

and draft service—maintaining quality from tank to consumer.

- Explain the purpose of beer clarification

- Identify common fining and stabilizing agents

- Describe methods for removing yeast, proteins, and haze-active compounds

- Understand carbonation methods (spunding, force carbonation, stone absorption)

- Differentiate packaging formats (kegs, cans, bottles) and their requirements

- Explain oxygen management and its importance in shelf-life stability

- Outline best practices for cold crashing, filtration, and final beer checks

Clarifying Beer: Cold Crash & Fining Agents

After fermentation, beer contains suspended yeast, proteins, polyphenols, and other haze-forming particles.

Clarification prepares the beer for filtration or packaging and improves visual appeal and flavor stability.

Cold Crashing

A cold crash rapidly chills the beer—typically to 32–36°F (0–2°C)—

causing solids to flocculate and drop out of suspension. Yeast and protein complexes sediment quickly,

reducing turbidity and improving clarification before filtering or racking.

Fining Agents

Finings bind to particles and help them settle. Common brewery finings include:

- Biofine Clear (silica sol): Removes yeast and protein haze; vegan-friendly.

- Isinglass: Collagen-based fining for brilliant clarity in cask ale.

- Gelatin: Strong fining for removing yeast across many beer styles.

- Irish Moss / Whirlfloc: Kettle finings that precipitate proteins during boiling.

- PVPP: Targets polyphenols responsible for chill haze and long-term instability.

Clarification reduces load on filters, improves flavor stability, and prepares beer for packaging.

Many breweries combine cold crashing + finings for optimal clarity before final processing.

Beer Filtration Methods

Filtration polishes beer by removing fine particles, yeast, and haze compounds that remain after clarification.

Breweries choose filtration systems based on beer style, desired clarity, and cellar workflow.

Diatomaceous Earth (DE) Filtration

DE filters use fossilized diatoms as a porous filtration medium.

They provide excellent clarity and are widely used in lager breweries.

DE requires careful handling and produces spent material that must be disposed of responsibly.

Cartridge / Sheet Filtration

Cartridge or sheet filters use disposable membranes or pads with defined micron ratings (0.5–5.0 µm).

These systems are ideal for:

- Final polishing before packaging

- Yeast and bacteria removal for sterile filtration

- Small to medium-scale breweries

Centrifuge Clarification

Centrifuges spin beer at high speed to separate solids via centrifugal force.

They:

- Recover 5–10% more beer per batch

- Reduce tank time and increase cellar throughput

- Preserve hop aroma better than tight filtration

- Can replace or minimize DE or pad filtration

Many modern breweries combine a centrifuge + polishing filter

to achieve maximum clarity while retaining delicate aroma compounds.

Stabilizing Beer for Shelf Life

Even after clarification and filtration, beer contains proteins, polyphenols, and starch-derived compounds

that can cause haze or instability over time. Stabilization is the final polishing step that ensures beer

remains bright, stable, and consistent throughout its shelf life.

PVPP (Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone)

PVPP binds with polyphenols—tannins that react with proteins to form chill haze.

It mimics yeast cell walls and attracts tannins, which are removed during filtration. Commonly used for:

- Light lagers

- Beers requiring long-term cold stability

- Export products

Silica Gel

Silica gel targets haze-active proteins but leaves foam-positive proteins intact.

Ideal for:

- Preventing permanent haze

- Improving clarity post-filtration

- Preserving foam quality

Stabilizing Enzymes

Enzymes such as Clarity Ferm and proteases break down haze-active proteins and gluten fractions:

- Prevent chill haze formation

- Lower gluten content

- Improve clarity even without filtration

Stabilizers are added either before filtration or directly in the bright tank.

Using PVPP + silica gel together provides comprehensive protection against both protein and polyphenol haze.

Carbonation in Beer

Carbonation influences mouthfeel, aroma release, foam quality, and overall drinkability.

Brewers select carbonation methods based on style, tank design, and packaging requirements.

Natural Carbonation (Spunding)

Spunding captures CO₂ naturally produced by yeast near the end of fermentation:

- Improves foam stability

- Reduces oxygen pickup

- Creates smoother, finer bubbles

Force Carbonation

CO₂ is injected into beer under pressure via a carbonation stone:

- Precise dissolved CO₂ control

- Rapid carbonation (minutes to hours)

- High batch-to-batch consistency

Stone Absorption / Diffusion

A microporous carbonation stone diffuses CO₂ as extremely small bubbles:

- Efficient absorption in bright tanks

- Ideal for highly carbonated styles

- Perfect for final adjustments before packaging

Most breweries use a hybrid approach—natural carbonation when possible,

followed by force carbonation to fine-tune dissolved CO₂ levels.

Review: Key Concepts in Beer Packaging

- Cold crash

- Finings

- Improves clarity & stability

- DE Filters

- Cartridge Filters

- Centrifuges

- PVPP

- Silica Gel

- Enzymes

- Spunding (natural)

- Force carbonation

- Carb stone diffusion

Packaging Into Kegs

Kegging is one of the most efficient and widely used methods of packaging finished beer.

Cleanliness, sanitation, and oxygen control are essential to preserving beer quality.

- Cleaning & Sanitizing: Kegs are washed with caustic, rinsed, and sanitized with steam or chemicals.

- CO₂ Purge: Removing residual oxygen protects beer from oxidation.

- Closed Transfer: Pressure transfers prevent oxygen pickup and maintain carbonation.

- Set Head Pressure: Keg pressure is adjusted to match final CO₂ levels.

- Leak Checks: Valves and gaskets are inspected for integrity and seal strength.

Keg packaging is fast, cost-effective, and ideal for preserving hop aroma, carbonation, and freshness.

Packaging Into Cans & DO Control

Canning offers portability, light protection, and outstanding shelf stability — but requires

strict dissolved oxygen (DO) management to preserve beer quality.

Critical DO-Control Steps

- Foam the Beer: Natural foam displaces oxygen in the headspace.

- Under-Lid CO₂: CO₂ blasts remove trapped air before seaming.

- Consistent Fill Height: Ensures minimal oxygen exposure.

- Seamer Accuracy: Proper seams prevent leaks and oxygen ingress.

- Low-Oxygen Transfers: Closed or semi-closed lines maintain TPO control.

A well-maintained canning line minimizes Total Packaged Oxygen (TPO) —

crucial for hazy IPAs, hop-forward beers, and any product requiring long-term freshness.

Final QA/QC Before Release

Before any packaged beer leaves the brewery, it undergoes critical analytical and sensory evaluation

to confirm consistency, stability, and overall quality.

Typical QA/QC Checks

- Dissolved Oxygen: Ensures stability, especially in cans.

- CO₂ Volume: Confirms carbonation matches style specs.

- Alcohol Content: Verified by hydrometer or lab analysis.

- Micro Testing: Detects contamination from bacteria or wild yeast.

- Sensory Panel: Evaluates flavor, aroma, clarity, and off-notes.

- Package Integrity: Checks seams, valves, gaskets, and pressure retention.

Only after passing these QA/QC checks is beer approved for distribution or taproom service.

Packaging Review: Test Your Knowledge

Flip each card to review the key concepts from kegging, canning, and QA/QC procedures.