New to Propagate Lab: check out our Seltzer Kit containing everything needed to make an award-winning seltzer!

Lesson 1: Grain to Glass

Module 1: Grain to Glass

The Brewery Process

The goal of this section is to provide an overview of the brewing process,

highlight its key ingredients, introduce its historical roots, and define many

of the terms used throughout brewing.

- Understand the 4 key ingredients in beer

- Recognize where each ingredient is used in the brewing process

- Name the main components of a brewhouse

Historical Overview

Beer Through the Ages

Beer has been brewed (and enjoyed) for more than 7,000 years, making it one of the earliest biotechnologies practiced by humans. From the moment early civilizations discovered that wet, sprouted grain could ferment into a pleasant drink, brewing became deeply connected to agriculture, culture, and community life.

It’s fair to say that the brewing process and the cereal grain barley are married to one another. Barley is uniquely suited for brewing — its husk protects the kernel during malting, its enzymes efficiently convert starch into fermentable sugars, and its flavor contributes to beer’s stability and drinkability. As early peoples began cultivating barley, brewing quickly spread alongside agriculture.

Early Civilizations:

The Sumerians, Mesopotamians, and Ancient Egyptians all brewed beer as part of daily life. The Hymn to Ninkasi (dating back over 4,000 years) is both a prayer and a beer recipe. Egyptian workers were even paid in bread and beer, and large-scale breweries existed along the Nile.

The Middle Ages:

As brewing moved across Europe, monasteries refined production through detailed recordkeeping, yeast reuse (long before microbes were understood), and the widespread adoption of hops as a preservative and bittering ingredient.

Lager Brewing & Innovation:

Central European brewers working in cool caves developed cold-fermented lagers, while advances in malting technology in the 1800s led to pale malt and iconic styles like Pilsner.

Scientific Era:

The 18th–20th centuries revolutionized brewing:

- Thermometers and hydrometers improved consistency

- Pasteur identified yeast as a living organism

- Refrigeration enabled year-round lagering

- Industrial automation expanded production

Modern Craft Brewing:

The late 20th century craft movement revived traditional methods, emphasized flavor diversity, and blended ancient practices with modern science. Today’s brewing world is richer, more innovative, and more globally connected than at any time in history.

The 4 Core Ingredients

Barley

Barley is the primary grain used in brewing. It undergoes malting to activate enzymes and develop the desired sugar content. It is one of a family of cereal grains which we will need to learn about. Like all plants, barley takes in sunlight and uses it to provide the energy required to convert carbon dioxide, water, and key nutrients from the soil into the energy that it needs to grow.

As it grows, it stores energy for later use in the form of starch. The plant can later break the starch back into sugars to provide energy for growth. As the plant matures and produces seeds, it packs them full of starch. The seed can use that stored energy later when it sprouts and grows into a new plant.

As brewers, we utilize the starch stored in the seeds (kernels) to power our beer’s fermentation. In order to do so, we malt the seeds — a process we’ll cover in depth in a future section. For now, it’s important to know that barley provides the starch (and ultimately sugar) for our brew.

While we are focused on barley, it’s important to note that it comes in many different varietals. What is a varietal? We can use a familiar agricultural example — apples — to think of varietals. Apples come in many shapes, sizes, flavors, and acidity levels. We use some apples for eating, others for baking or fermenting into cider. Similarly, barley varietals differ in starch, protein, and enzyme levels, allowing brewers to tailor recipes to specific beer styles.

Over the past century, just a few barley varietals have dominated the brewing industry, but craft malsters are now reintroducing historic varietals once again. There are also two major types of barley used in brewing: 2-row and 6-row, each with distinct starch and enzyme characteristics.

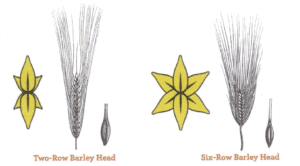

Barley Types

There are two types of barley — 2-row and 6-row.

Six-row barley is sometimes referred to as Distillers Malt because it contains

a greater enzymatic potential than 2-row barley.

As you can see in the image, 2-row kernels grow two per level on the plant’s stalk,

while 6-row kernels are more tightly packed. This allows 2-row kernels to be plumper

and store more starch than 6-row.

Brewers generally prefer 2-row malt for its higher starch content and smoother flavor.

However, when using grains low in natural enzymes (like wheat, corn, or rye),

6-row barley can help by contributing additional enzymatic power to convert starches into fermentable sugars.

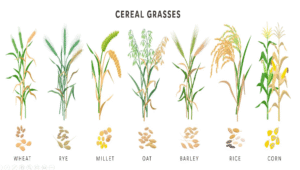

Cereal Grains

Barley is just one of many cereal grains, and you’re likely familiar with most of the others. These grains share common traits with barley, but subtle differences make a huge impact on how they’re used in brewing. The cereal grain you’re probably most familiar with is wheat—used for baking because of its high protein content. In 1516, Germany’s Reinheitsgebot (“purity law”) limited wheat in brewing, partly to preserve it for bread production.

Other cereal grains encountered in brewing include oats, rye, rice, and corn. Oats add a silky, full mouthfeel (think creamy oatmeal stout). Rye contributes a spicy character, as seen in Roggenweizen (a rye-based version of hefeweizen). Corn and rice—used in many popular American lagers—raise alcohol content without adding much body, and are cost-effective for large-scale production.

Barley and brewing are inseparable partners. The process of brewing has evolved around barley’s unique traits. Here’s why barley is uniquely suited for beer production:

- Nutrients and Fermentation: Barley has balanced proteins, sugars, and nutrients for healthy yeast fermentation. Rice and corn lack sufficient protein for robust fermentations.

- Enzymatic Power: Barley provides enough natural enzymes to convert starches into sugars during mashing. Rice and corn do not.

- Natural Husk: Barley’s husk aids in separating liquid wort from solids during lautering. Grains like corn, rye, and wheat lack this husk structure.

- Compatible Temperatures: Barley’s saccharification temperature aligns with its mashing temperature. Grains such as corn require higher temperatures that would destroy essential enzymes.

Together, these factors explain why barley and brewing have developed side by side through history. From malting and mashing to fermentation and packaging, the entire brewing process is designed with barley in mind—a perfect example of nature, science, and craft working in harmony.

Water

More than 95% of a beer’s weight is water. Water is often called the universal solvent — it can’t dissolve everything, but it can dissolve a vast range of compounds. When something dissolves, it breaks apart and becomes part of the solution.

Beer contains many dissolved compounds: ethanol (3–15%), residual sugars and dextrins that add body, glycerin from yeast that improves mouthfeel, and flavor and aroma compounds from both yeast and hops. Together, these create the complex character of beer.

Water also participates directly in the chemical reactions of brewing. It influences flavor, enzyme activity, yeast health, and even color. Because of its importance, an entire module in this course will focus on brewing water and its chemistry.

Historically, local water profiles shaped entire beer styles. Before water chemistry was fully understood, brewers were limited to the water available in their region. Hard, mineral-rich water often favored darker beers, while softer water made it easier to brew pale, hop-forward styles. Understanding water composition is key to mastering beer flavor and consistency.

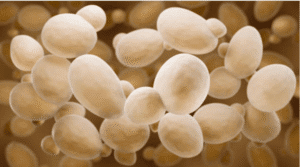

Yeast

Yeast is a single-celled fungus responsible for transforming the sugars in wort (unfermented beer) into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and hundreds of other flavor compounds found in finished beer.

The yeast most commonly used in brewing belongs to the genus Saccharomyces. The name is derived from Latin and Greek roots: Sacch meaning “sugar,” and myces meaning “fungus.”

This “sugar fungus” consumes the sugars present in wort and converts them into ethanol, CO₂, and other metabolites.

Throughout this course, we’ll explore fermentation in detail, but for now, focus on yeast’s essential role: it metabolizes sugars to produce energy for growth and reproduction—creating alcohol and carbonation in the process.

In short, yeast takes simple sugar water and turns it into beer, while conveniently carbonating it for us. It’s one of the smallest yet most important players in the brewing process.

Hops

The final key ingredient in beer is hops. The hops plant is a climbing bine that grows from rhizomes. Its closest relative is the cannabis plant, and hops produce many of the same types of oils and resins found in that family.

Before hops were introduced to brewing, a variety of herbs and spices were used to add flavor and preservation. Without hops, beer is overly sweet and spoils quickly. Once brewers discovered hops’ benefits, they became the preferred ingredient — extending beer’s shelf life and balancing its sweetness with bitterness.

What makes hops such an excellent addition to beer? Several things:

- Bitterness: Hops add bitterness that balances residual sweetness from malt sugars.

- Flavor: Hops contribute pleasant flavors — citrus, pine, resin, spice, and floral notes — depending on the variety and timing of addition.

- Aroma: Many of the same flavor compounds also provide vibrant, aromatic qualities to beer.

- Preservation: When boiled in wort, hops contribute bacteriostatic properties — they inhibit bacterial growth and help preserve beer for storage and transport.

Hops are one of the most dynamic and exciting ingredients for brewers to work with. Later in this course, we’ll dive deep into hop varieties, timing, and techniques to help you get the most from this essential plant.

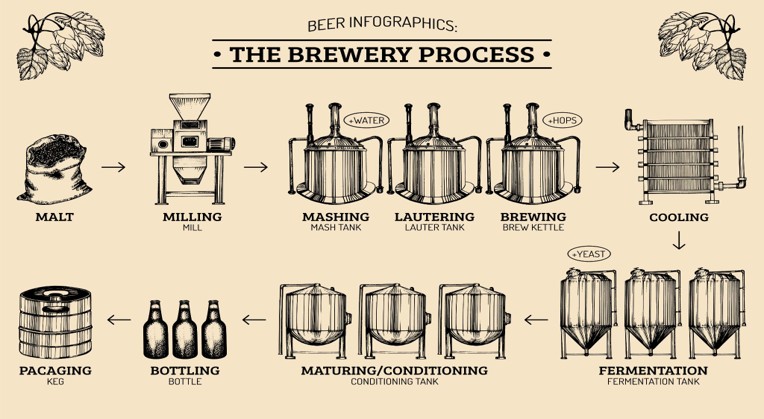

Now that we understand beer’s ingredients, let’s look at how they come together in the brewery. Brewers generally divide the process into two stages: the Hotside (wort production) and the Coldside (fermentation, maturation, and packaging).

Brewing typically begins the day before, when the brewer mills the grain, checks inventory, and prepares the brewhouse. Clean equipment and pre-heated water ensure a smooth start to brew day.

On the Hotside, the brewer mixes crushed malt with hot water to create a mash. Enzymes naturally present in the grain convert starches into fermentable sugars. After about an hour, the sweet liquid (wort) is separated from the spent grain in a process called lautering. The wort is then boiled, and hops are added at various times for bitterness, flavor, and aroma.

The Coldside begins once the wort is cooled—typically through a heat exchanger—to fermentation temperature. Oxygen is introduced, and yeast is pitched. Within 24–36 hours, fermentation begins as yeast metabolizes sugars into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and other flavor compounds.

After two to three days, “green beer” is produced. It still contains off-flavors like acetaldehyde (green apple), so the beer is conditioned for another 5–7 days to mature, clarify, and balance. Once ready, it is packaged and served.

While this is a simplified overview, it covers the main stages of brewing—from grain to glass—and lays the foundation for understanding each step in greater detail.

Conclusion: From Grain to Glass

The journey from grain to glass is a testament to the harmony between nature, science, and craftsmanship. At the heart of brewing lies a deep understanding of the four core ingredients — barley, water, yeast, and hops — each playing a critical role in shaping the character of beer.

We’ve explored how barley, the backbone of brewing, provides essential starches and enzymes that make it uniquely suited for beer production. Water influences flavor, fermentation, and even the styles that can be brewed. Yeast transforms wort into beer through fermentation, creating alcohol, carbonation, and countless subtle flavors. And hops deliver balance, aroma, and natural preservation.

By connecting these ingredients through each stage of the brewing process — from milling and mashing to fermentation and packaging — brewers turn raw materials into a crafted product that reflects both tradition and innovation.

This module provided a high-level overview to set the stage for deeper dives into every ingredient and process step in future lessons. With this foundation, you’re now ready to appreciate both the art and science behind every pint.

🍻 Cheers to the start of your brewing journey!